STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY: GROWTH FAULTS AND BASIN EVOLUTION

INTRODUCTION

Structural geology plays a vital role in understanding the deformation and structural framework of the Earth’s crust.

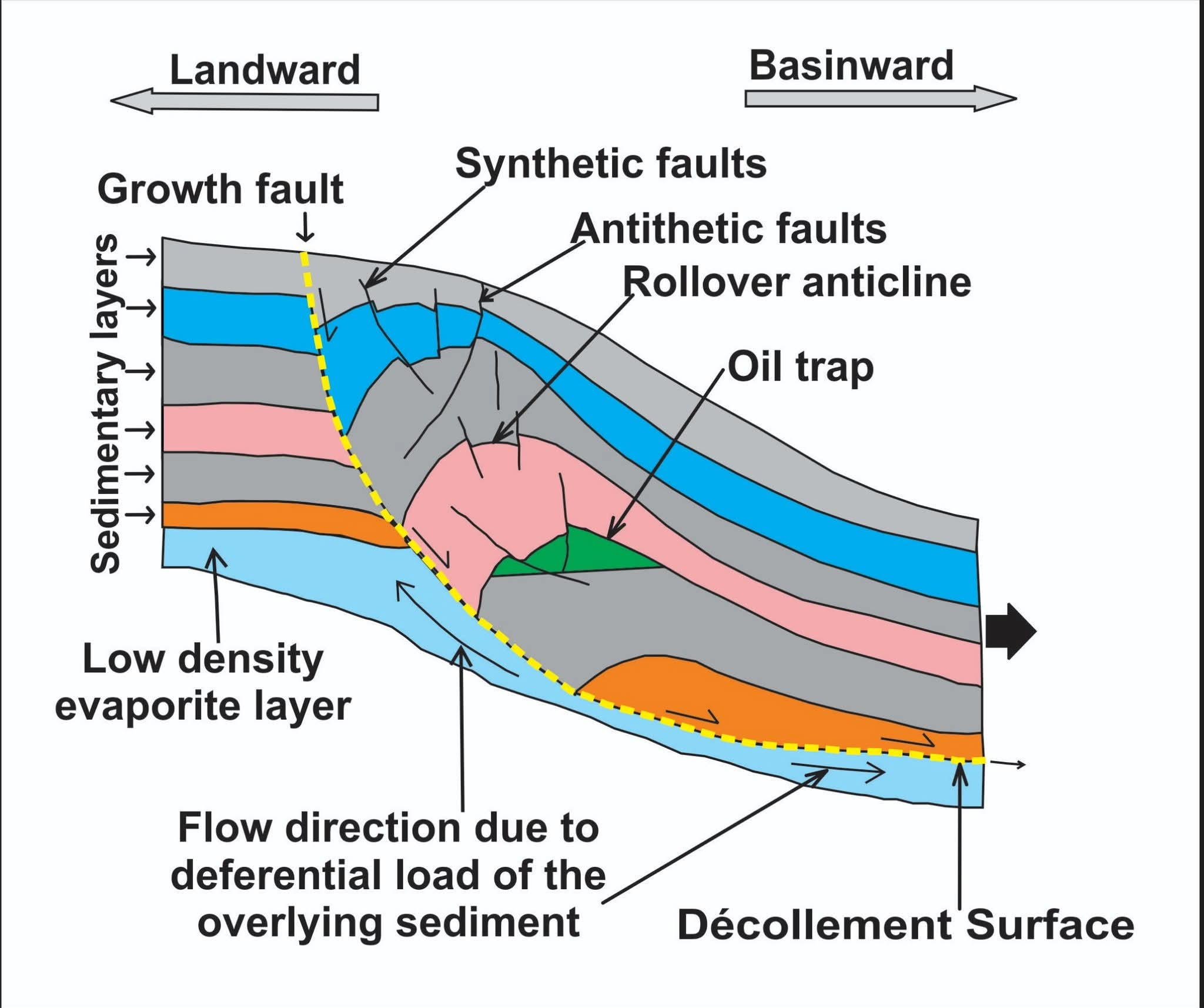

Among the most fascinating features studied in sedimentary basins are growth faults, which are major structural elements that control sediment deposition, basin geometry, and even hydrocarbon accumulation.

Growth faults are large-scale normal faults that develop contemporaneously with sedimentation.

They are particularly common in passive continental margins, deltaic environments, and extensional tectonic settings.

Their evolution directly influences the shape, depth, and sedimentary fill of basins, thereby affecting basin evolution over geological time.

DEFINITION AND BASIC CONCEPTS

A growth fault is a type of normal fault that forms during active sedimentation.

The term “growth” refers to the fact that as sediments accumulate, the fault continues to move, resulting in thicker sedimentary sequences on the downthrown block than on the upthrown block.

This uneven accumulation produces characteristic features such as rollover anticlines, listric fault geometries, and associated secondary faults.

Growth faults usually dip toward the basin center and flatten with depth, often merging into a detachment or décollement surface.

FORMATION AND MECHANISM OF DEVELOPMENT

The formation of growth faults is closely related to sediment loading, differential compaction, and gravity-driven deformation.

When sediments are deposited rapidly, especially in deltaic or continental margin settings, the underlying weaker layers such as shale or evaporite can fail under the weight.

This leads to slumping and extension of the overlying sediments, initiating faulting.

Continued sedimentation causes progressive movement along the fault plane, leading to the accumulation of thicker sequences in the downthrown block.

In some cases, tectonic extension also contributes to fault initiation. In rift basins, crustal stretching and subsidence create accommodation space that promotes fault-controlled sedimentation.

The simultaneous processes of deposition and faulting maintain the “growth” nature of the fault.

CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES OF GROWTH FAULTS

Growth faults display distinctive structural and stratigraphic features, including:

Thickening of Sedimentary Units:

The sedimentary beds are thicker on the downthrown block and thinner on the upthrown block.

Rollover Anticlines:

The downthrown strata often bend or roll over toward the fault plane, forming traps that can accumulate hydrocarbons.

Listric Fault Geometry:

The fault plane is typically curved, steep near the surface but flattening at depth.

Synsedimentary Deformation:

Deformation occurs at the same time as sediment deposition, evident from the continuous bedding planes across the fault.

Fault-Related Growth Wedges:

The wedge-shaped sedimentary sequences adjacent to the fault record progressive movement during sedimentation.

BASIN EVOLUTION AND GROWTH FAULTS

Growth faults have a profound influence on basin evolution.

They control sediment accommodation space, subsidence rates, and stratigraphic architecture.

In deltaic systems such as the Niger Delta, the Mississippi Delta, and the Gulf of Mexico, growth faults determine the distribution of depocenters, the migration of sedimentary facies, and the location of potential hydrocarbon traps.

During basin evolution, the interplay between sediment loading, compaction, and faulting drives differential subsidence.

This process results in complex basin architectures composed of multiple fault blocks and rollover structures.

Over time, older faults may become inactive as new faults develop basinward, reflecting the continuous progradation of the sedimentary system.

In passive margins, growth faulting is often associated with salt tectonics.

Evaporite layers, such as halite or gypsum, provide a detachment surface that facilitates movement.

Salt withdrawal beneath growing faults can amplify subsidence, further influencing basin geometry.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS IN GEOLOGY

Understanding growth faults is crucial in petroleum and energy exploration.

Many hydrocarbon reservoirs are located in structural traps formed by growth faults and associated rollover anticlines.

The sealing capacity of the fault plane, combined with the permeability of adjacent sands, determines hydrocarbon accumulation.

Geoscientists use seismic interpretation, well data, and structural modeling to identify these traps.

In addition, growth faults influence groundwater flow, mineral migration, and geothermal energy systems.

Their movement can create zones of enhanced permeability, allowing fluids to circulate.

In engineering geology, understanding growth fault activity is vital for assessing ground stability and infrastructure safety in regions prone to subsidence.

MODERN TECHNOLOGIES IN THE STUDY OF GROWTH FAULTS

Advancements in technology have transformed how geologists study growth faults and basin evolution.

3D Seismic Interpretation:

High-resolution three-dimensional seismic data enable geoscientists to visualize subsurface fault geometries, rollover structures, and stratigraphic relationships with great precision.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS):

GIS tools assist in mapping fault patterns, sediment distribution, and basin-scale deformation.

Remote Sensing and Satellite Imagery:

Modern satellite data help detect surface expressions of faulting and subtle geomorphic changes associated with active growth faults.

Basin Modeling Software:

Numerical simulations allow the reconstruction of basin evolution, sedimentation rates, and fault growth history through geological time.

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence:

These modern approaches are increasingly used to analyze seismic data, predict fault patterns, and optimize exploration strategies.

GROWTH FAULTS IN THE NIGER DELTA

A classic example of growth fault development is found in the Niger Delta Basin, Nigeria.

The delta exhibits a complex network of listric normal faults that formed due to rapid sediment loading on mobile shale layers.

These faults have created numerous rollover structures that serve as hydrocarbon traps.

Continuous delta progradation has shifted fault activity seaward, illustrating the dynamic link between sedimentation and structural evolution.

The study of Niger Delta growth faults provides valuable insights into reservoir distribution, fluid migration, and regional tectonics.

Oil companies operating in the region rely heavily on seismic interpretation and 3D modeling to identify fault-bounded traps and optimize drilling targets.

IMPACT OF GROWTH FAULTS ON SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS

Growth faults not only affect subsurface structures but also shape surface and near-surface environments.

They control river courses, deltaic lobes, and coastal morphology.

Active faulting can create accommodation space for wetlands and lagoons, influencing modern sedimentary processes.

Over geological time, these structures contribute to the stratigraphic complexity of basins and the distribution of sedimentary facies.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite technological progress, understanding growth faults still poses challenges.

Fault sealing behavior, for instance, remains complex and unpredictable.

Accurate prediction of fluid migration pathways requires integration of structural geology, petrophysics, and geomechanics.

Future research should focus on real-time fault monitoring using InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar), time-lapse seismic surveys, and high-resolution geophysical imaging.

Interdisciplinary collaboration between structural geologists, geophysicists, and basin modelers will continue to enhance our understanding of growth fault dynamics and their broader implications for natural resource exploration and environmental management.

CONCLUSION

Growth faults are key structural features that play a dominant role in shaping sedimentary basins and controlling their evolution.

Their influence extends from the surface to deep subsurface levels, affecting sedimentation patterns, hydrocarbon accumulation, and crustal deformation.

A comprehensive understanding of growth faults, supported by modern analytical tools and technologies, provides valuable insights into basin development and resource potential.

As exploration moves into more complex and deeper settings, the study of growth faults will remain central to structural geology, basin analysis, and sustainable resource exploitation.